COP28 - A personal insight

What is a COP

The 28th Community of Parties (COP28), the annual global summit for climate change, got concluded some days ago in Dubai, UAE. It comprises three major events in one: A high-end national assembly (identical to the ones conducted at the United Nations meetings), a scientific congress mainly – but not limited to – climate related science, and a major Fair (similar to EXPO) that hinges on sustainability and all its expressions. COPs are in fact an annual update of science data with regards to climate change as well as a point of reporting and reflection to each country’s achievements, promises and fallbacks, compared with their original climate targets as agreed on the latest commitments, namely the Kyoto Protocol (1997) and the Paris Agreement (2015).

The Parties consist of national delegations (usually led by Ministers for the Environment, Energy, Planning and the like), representatives of local authorities (Mayors, Council specialists etc), scientists with fields related to climate change, sustainability and the environment (both natural and human-made), activists, representatives of indigenous populations, farm/land workers, minorities, as well as individuals representing secondary and tertiary sector entities. Apart from national and sub-national authorities, all other delegates participate through affiliations with specific parties; groups of advocates with specific agendas, strategic goals and actions, thus composing a wide community of voices and interlocutors.

That has been my first participation at a COP, actually representing two organizations: The International Society of City and Regional Planners (ISOCARP) of whom I am a member and for whom I acquired the original COP28 registration and clearance, and Abu Dhabi University as my main affiliation as an Associate Professor of Architecture and Urbanism. Although I was registered as an “Observer”, a status under which one is not allowed to conduct presentations but mostly observe and raise questions, I had been asked by the Parties that I was associated with to present specific pieces of my research work, pieces that fitted the discussion needs within specific sessions. In one of them, an invitation by the UN Habitat, I was unable to go due to schedule inabilities. In a second one, I was organizing a panel discussion/presentation on my awarded Architecture Workshop with Year4 students of BISAD, on behalf of ADU, within the Pavilion of the UAE Ministry of Education (please check the next presentation on this website).

The whole event lasts for two weeks, while each day comes with its own theme. Following a plethora of parallel presentations, sessions, discussions and debates that take place within all buildings of the venue, every single Party and Session Chair involved forward the strongest of outcomes and findings towards a second round of debate and the formation of thematic manuscripts with common grounds, observations and eventually proposals, to be conducted by a wider body of national delegations. The manuscripts – more political, diplomatic or legal documents rather than scientific ones – are set to be voted, paragraph by paragraph, following a highly cynical process of seemingly endless edits, cuts, additions and rewordings. On the last day, all those thematic documents usually lead to a main one that accumulates all major points and provides a strategic pathway for all participants and for the COPs to follow.

How was COP28 different?

One may ask though, what makes COP28 that important? Did it manage to stay on track and build up on the work of all past COPs? Did it manage to elevate itself above and beyond the “blah blah” and the politically generic yet naïve wishful thinking and address its almost permanent criticism? A criticism that intensified just before the COP28 opening on the announcement of its Presidency, Dr. Sultan Al Jaber, CEO of ADNOC, Abu Dhabi’s National Oil Company.

Every COP builds upon the work of the preceding ones. Dubai’s COP28 built upon the foundations set in Glasgow and Sharm El Sheikh and can claim success on achieving and implementing specific actions.

First of all, the recognition of cities and subnational (or trans-national) regions with specific environmental characteristics as equal participants apart from their national delegations, a conquest that underlines and reflects the dynamic participation of urban areas and of sensitive, protected habitats on the overall climate change stage. With regards to cities, humanity has already crossed the psychological threshold of 50% of its entire population living in urbanized areas, a percentage projected to reach 70% by 2050, thus indicating an escalating pressure in demand for actual space, housing, infrastructure, resources, labor, quality of life and social justice. Furthermore, there is an ever-growing list of cities that display scale economies, population diversity and a high concentration of tertiary services including innovation and research that supersedes the ones of entire countries and has led to a request for an independent voice. On this direction, the Party that has been pushing the most, the Local Governments and Municipal Authorities (LGMA) Constituency commended “the political commitment of nation-states and the COP28 Presidency to engage with local and other subnational governments on climate planning, financing and implementation as one of the most significant outcomes for local and other subnational governments since the Paris Agreement. As the LGMA jointly advocated leading up to and throughout COP28, effective multilevel action and sustainable urbanization will be among the most important tools to support nations in delivering their commitments adopted and announced here in Dubai”[1]. Therefore, it has been a special and historic moment seeing Municipality officials sharing the stage with national delegates.

Second, the introduction of a Loss and Damage Fund that will directly support areas affected by extreme weather incidents. Although it had been asked for and debated during the last COPs, the lack of a trustworthy and globally applicable platform were the main reasons of its delay. Its implementation eventually became possible through the involvement of the World Bank – in lack of other alternatives – a decision that raised a second round of criticism due to its track record in matters of transparency and colonial practices. Several countries also raised or pledged direct funds (instead of indirect lending programs) of almost one billion USD, an amount that lies far away from the 400 billion USD estimate that is calculated for covering the needs up to date. More criticism was expressed at this point by the countries at risk that demanded a clearer “pollutants pay” directive, on the fact that fossil fuel economies present a one trillion USD profit and on the sad confession that “while we fiddle, nature will continue to send us bigger and bigger invoices”[2]. This reiterates two more severe issues of the Loss and Damage Fund:

· First, the fact that its description is limited to a generic statement of financial tools, insurance values, intentions and initiatives but ignores its social component: direct access to affected communities, mid-term restoration plan on employment and primary sector, small-scale economies and mitigation thoughts on climate migration.

· Second, the hype generated on the Fund has unfortunately shifted priority and focus from the Adaptation Plans that should precede this Fund both in terms of time sequence and of importance (under the logic that Adaptation equals to prevention whilst the Loss/Damage Fund equals to recovery).

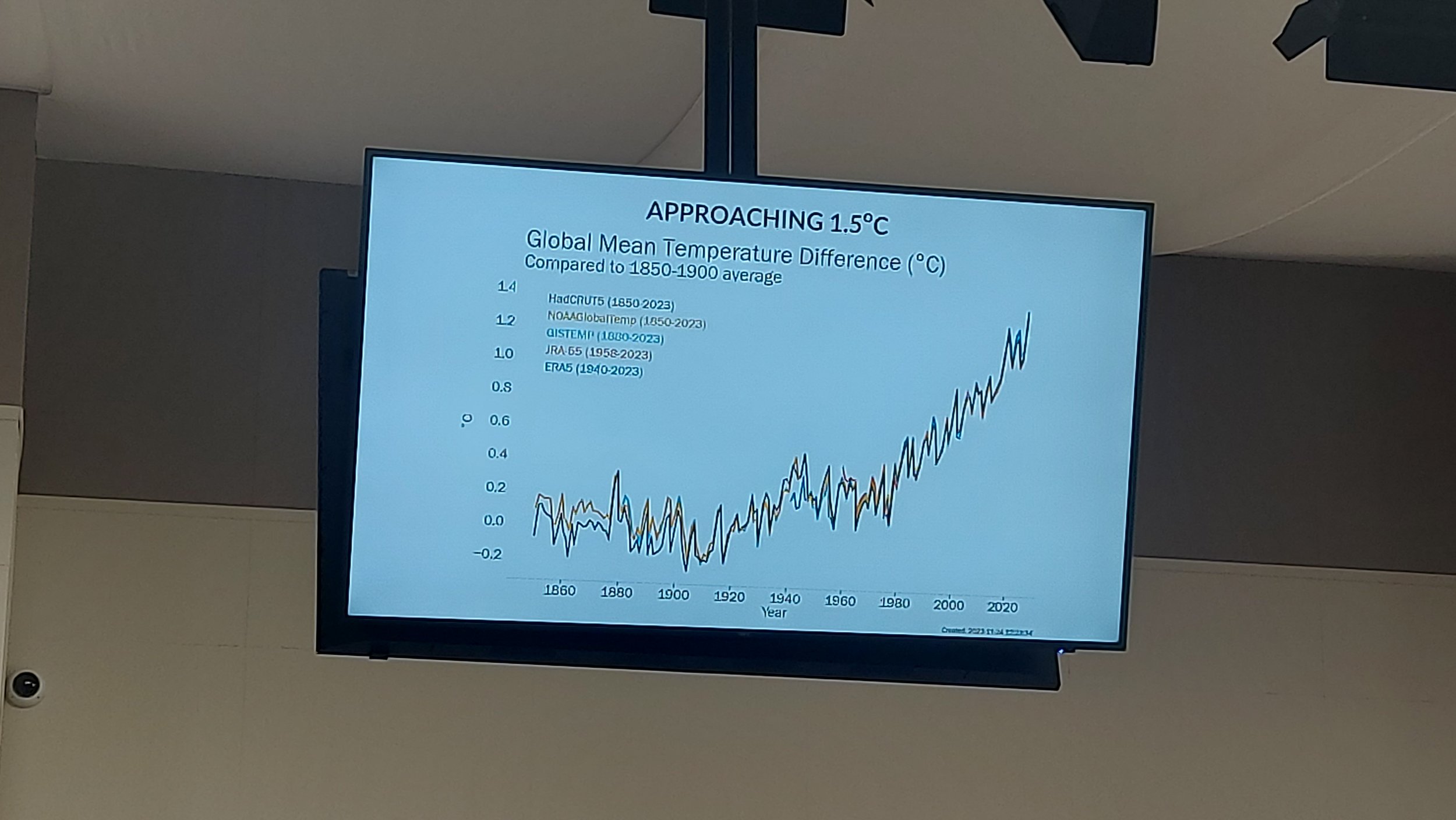

Third, the fact that the voice of Science has never been as dramatic, intense, unified and filled with agony as it has been now, on the existing condition and the pathways ahead. Until now, there have been three major scenarios of action and related mean temperature increase at the global scale until 2050: Up to one and a half degree Centigrade (1.5°C), up to two and a half or three degrees (2.5°C - 3°C) and of course a destructive “business as usual” scenario. The two first ones shall still incur remarkable consequences on global climate balance, however even this one degree could make a major difference. Unfortunately, a report that shocked everyone who read it mentions that we have already reached a temperature increase of 1.4°C under a significant growth rate – a number that lies too close to optimistic scenario’s target and too early, much earlier than the set horizon.

The dramatic ending

The COP28 days were passing by on a worryingly predictable way, as major gaps had started manifesting themselves. A scientific gap for active climate research between global north/south institutions, with the north accumulating the lion’s share on funding, authors, research teams’ affiliations and publishers. This leads to an alienation from the context itself and from strengthening ties between institutional knowledge with local communities. Several culprits were mentioned, including technological, infrastructural and institutional (administrative, bureaucratic and governance) obstacles.

An even wider gap was prevalent: the one on narratives. Whilst the scientific and the social ones have started to converge through an emphasis on localization, the narratives, language, intentions and motivations between those two and the political parties, the national delegations and the tertiary servicers could not be more distant. On the third last day of COP28, only one out of the twenty four thematic manuscripts were agreed and voted and five more were following suite.

On the same note, I was honored and lucky to attend the Plenary of the People, the one dedicated to the parties and representatives that voice the voiceless: workers of land and sea, blue collar workers, indigenous people, ethnic minorities, socially and climatically displaced, war victims, children. The Plenary strongly, passionately and unequivocally voted a major statement on demanding ceasefire and liberation of Palestine, underlining that there can be no climate adaptation without climate justice and no climate justice without human rights. The Plenary asked all authorities not to price-tag air, land, water, humanity and nature, and halt commodifying indigenous resources. It demanded an overall system change, as the system that now seeks for diplomatic solutions is the one that generated those conditions in the first place, referring to a multitude of cases of human exploitation and of natural resources’ depletion through colonial practices of blinded capitalism and neoliberalism. The energy and agony forged on the faces of all plenary participants was contrasting the one of national representatives.

The last day of the Summit began with the main draft remaining generic enough, receiving the rage of many countries of the Global South and of scientific parties. Apart from the issues aforementioned with regards to the Loss and Damage Fund, there was little to no development on the Adaptation Plans and their prevention role – that should precede the Fund in both time and importance and hopefully alleviate it – especially with regards to their incorporation on all governance scales (national, subnational, municipal) and methods (global or sectoral). Furthermore, there was no courageous commitment on the major issue of production and consumption of fossil fuels. Several scientific parties proposed the introduction of a strong wording (“fossil fuel phase-out”), triggering a backstage reaction from OPEC against it, a development that generated major, severe and even diplomatic criticism at all levels. Indian and Pacific Ocean island countries referred to this as their “death penalty” and most media networks referred to a hypocritical stance of oil-producing countries[3][4]. Criticism and concern escalated even further when the announcement on the next COP took place, as Azerbaijan is an equally major oil/gas producer and advocate.

The last day ended fruitless. COP28’s optimistic start was replaced by feelings of frustration and emptiness. On the People’s Plenary, one of the most recurrent questions every speaker was addressing was “why are we still going to COPs”. Under the weight of the Summit’s abasement and the validation of all criticism posed with regards to the hypocrisy of the oil/gas industry, there was a late announcement for a one-day extension of the COP for the negotiations to continue. On that extra day, the closing Plenary took place. Despite odds, the Presidency conveyed a message of celebration; all countries and parties have risen up to the occasion and have agreed on a final draft, following significant recedence. However, initial celebrations were soon replaced by serious allegations and objections to both the process and the content of the draft’s formation and agreement: Countries such as Samoa, Marshall Islands, Venezuela and Bolivia protested and argued that they were not present when the draft was voted, that the wording “fossil fuel phase-out” was indeed replaced by a more moderate and less binding “transition away” one, and that a number of voted paragraphs on the apportionment of the dysfunctional Carbon Market were directly opposing the Paris Agreement. Several other countries followed.

The Plenary concluded and the draft – undernoted with all those remarks and objections – was voted to form the “UAE Consensus”, the step towards the COPs to follow. However, does this justify the celebration? Can someone dub the COP28 a successful one? Or, to rephrase, are COPs able to reflect – on their specific, current setup – the global agony and the local voices, the political and the social, the particularities of 200 nations and the demographic dynamics?

Eventually, the voted document of COP28 contains a description for an optional withdrawal from fossil fuels, without further detailing though with regards to production and/or consumption. It can boast for the implementation of the Loss and Damage Fund, albeit with plenty of grey areas and vital questions on the application methodologies to be addressed. Adaptation Plans are unfortunately still not well defined, prioritized and detailed enough, but, on the other hand, cities and subnational regions are now acknowledged as equal parties and speakers, with direct access, participation and authority to those Plans. The system of parallel sessions, reporting, thematic and general plenaries, participation and voting and of course all in-between transition has failed its test on transparency and democracy (i.e. on the way drafts were openly shared prior and throughout voting negotiations), but on the other hand has embraced all voices to be heard. What really had an impact on me though was the contrast between the cynical and mystical voting negotiations amongst national delegations and the passionate, inclusive people’s plenary and its direct democracy approach that reminded me of the contrast between the Greek “failed state” and the beautifully restructured Icelandic governance. As many constituencies kept mentioning, a proper climate response should need a proper systemic change.

What’s next?

So how do the COP28 decisions affect or should affect architecture and urbanism, the academia and the industry?

First of all, it must be made clear that the motto “let’s act together” should be taken literally and materialize equitably throughout the society and its activities, throughout the scales of reference, starting from the little, quotidian things at home and from education.

Cities should prepare for both scenarios and provide adaptation strategies depending on their contextual risks. This would include updated master and framework plans that should reconsider low density urban sprawl, horizontal segregation and urbanities of exclusion, gentrification, automobile monopolies and roadscape divisions. It would also include a complete approach revamp with regards to waterfronts and the incoming realities of sea level rise, flash floods and other risks related to water (or its depletion). Subnational regions and Countries should work together with cities on such strategic plans, in order to fully implement an osmosis of nature and the urban in favor of the former, by re-introducing notions as porocity, mobility through density and open, democratic, participatory, bottom-up approaches on physical design. Controlling urban sprawl also means incentivizing low-scaled, rural life that would prevent from desertification and improve food safety. Furthermore, it also means more areas and resources for protection and conservation, away from the sirens of luxurious “growth”.

Architecture as a profession – together with all counter-assisting disciplines – should become more aggressive in terms of sustainability and pass beyond passive strategies, to active ones (without neglecting the former). Architects, together with developers, authorities and eventually clients, should rise up to the occasion and abolish the commodification of fundamental rights (such as housing and the public space), the everything-but-sustainable, post-modern, superficial-artificial, lifestyle architecture, and embrace a new beautiful.

Academia should step up as well. Many programs and syllabi need to adapt. There can be no Architecture Program that doesn’t include carbon footprint calculations for each design, that doesn’t teach urban regeneration (but advocates for a “tabula rasa” design), that treats architecture as an act of instagrammable hedonism at the expense of any respect to locality. It should empower its faculty to more funded research – thus enabling capacity building and an emphasis to the human capital. In return, cities and countries should trust the Academia more, share information and open up to synergies as a long-term investment through education, research and innovation.

However, all those steps would mean very little unless the system itself that has brought humanity into this very threshold changes. Today, humanity still conducts wars, still prioritizes profit to its future, still raises walls and false divisions, still rejects accountability. Tomorrow, any climate response should begin with justice: social and climatic one.

[1] LGMA statement (14/12/2023): https://www.cities-and-regions.org/wp-content/uploads/cop28-outcomes-lgma-statement-final.pdf

[2] Debra Roberts, IPCC Plenary, December 3rd 2023, COP28.

[3] Abnett K. et al., (December 10, 2023), “COP28 clashes over fossil fuel phase-out after OPEC pushback”, https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/opec-members-push-against-including-fossil-fuels-phase-out-cop28-deal-2023-12-09/

[4] Harvey F. et al. (December 11, 2023), “Cop28 draft climate deal criticized as ‘grossly insufficient’ and ‘incoherent’”, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/dec/11/cop28-draft-agreement-calls-for-fossil-fuel-cuts-but-avoids-phase-out